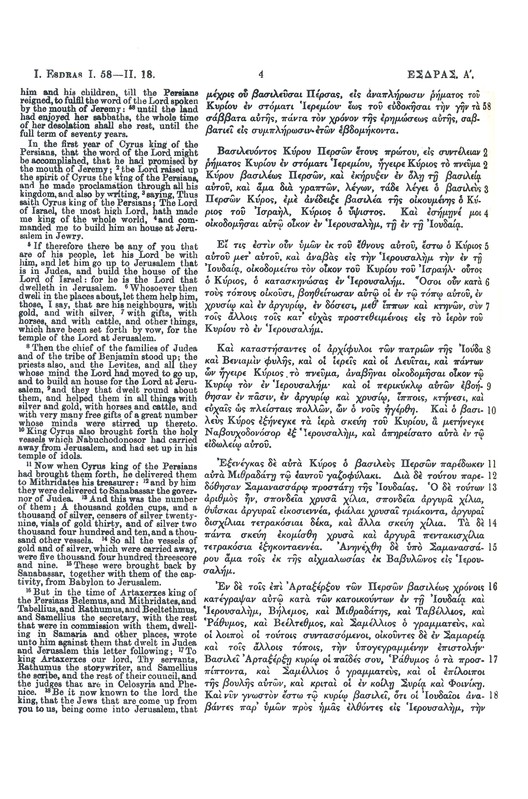

The Apocrypha Has Always Been Rejected By The Jews As Scripture The Jews have never considered these works to be divinely inspired. On the contrary, they denied their authority. At the time of Christ we have the testimony of the Jewish writer Flavius Josephus that they were only twenty-two books divinely inspired by God. The Septuagint with Apocrypha: Greek and English. L., Sir Brenton. Authoritative in the early Church, so it is worthy of our study today. This book contains the entire Greek text of the Septuagint, including the Apocrypha, along with an English translation.

THE SILENT CENTURIES

The Religious Literature

of the 'Intertestamental' Period

(The Apocrypha and Septuagint)

(Post-Maccabean Writings) (Septuagint)

During the 400+ 'silent centuries' a great deal of religious literature was produced. The Apocrypha, the Pseudepigrapha, the Septuagint, and the writings of the Qumran community -- the Dead Sea Scrolls -- are only a few of the better known examples of the type of sacred literature produced during this period. Some of the writings from this era are of great religious and historical significance; others are less so. All of them, however, shed light upon the thinking of their time, and are thus of importance to a better understanding of this historical period.

Perhaps the most significant collection of intertestamental writings is the Apocrypha, which means 'doubtful.' They are so characterized because very few actually accept them as inspired of God; they are of doubtful origin. The ancient Jews never accepted them as part of the Old Covenant canon, nor did the early church. Most scholars characterize them as 'a lower level of writing' since they contain numerous historical and geographical inaccuracies and anachronisms, and because they 'do not breathe the prophetic spirit so evident in Canonical writings.'

The Apocrypha is accepted, however, by the Roman Catholic Church, although they were not declared to be inspired of God (thus making them authoritative as recognized Scripture) until the Council of Trent (1546 AD). The Catholics, even given this declaration of inspiration, only include about half the books of the Apocrypha within their versions of the Bible. Indeed, some scholars feel the only reason the Catholic Church declared these writings to be inspired in the first place was to spite Martin Luther, who opposed them.

The Westminster Confession (1643 AD) states: 'The books commonly called Apocrypha, not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the Canon of Scripture, and are therefore of no authority in the Church of God, or to be any otherwise approved or made use of than other human writings.' The Anglican Church, in its Thirty-nine Articles, takes a mediating position between the Protestant and Catholic viewpoints: 'The Church doth read (the Apocryphal books) for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to confess any doctrine.' It should be noted that the Jews, whose literature and history this is, do not accept these books as being inspired, and thus they are not a part of their Scripture.

Interestingly enough, the Apocryphal book of II Esdras, which was probably written about the time the apostle John was penning the book of Revelation (the end of the first century AD), displays an awareness of the acknowledged and accepted OT canon of that time. In II Esdras 14:44-48 there is a distinction made between the recognized canonical books (the 39 books of the OT which we have today) and an additional 70 books which were to be 'kept back' and not given into the hands of the common people. These apparently were the disputed Apocryphal writings.

Following is a list of the major Apocryphal books, along with their date of composition (according to the widely accepted scholarship of W.O.E. Oesterley) and a brief summary of their contents.

THE PRE-MACCABEAN WRITINGS

I ESDRAS (300 BC) --- Esdras is the Greek form of Ezra. This book is a compilation of passages from Ezra, II Chronicles, and Nehemiah. It relates a series of historical episodes from OT history, beginning with the Passover celebration in Jerusalem instituted by King Josiah (c. 621 BC) and ending with the public reading of the Law by Ezra (c. 444 BC). It also contains additional, non-biblical legends about Zerubbabel (known as the Tale of the Three Guardsmen). Its purpose was to portray the liberal, benevolent natures of Cyrus and Darius toward the Jewish people, perhaps hoping the Ptolemies would follow the same practice.

TOBIT (250 BC) --- This book is a romance; a book of religious fiction, which is entirely devoid of any real historical value. It is the story of a rich young man of Israel who is taken captive and sent to Nineveh at the fall of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BC. An angel leads this young man to a virgin-widow (she had lost seven different husbands -- all on their wedding day -- when they were killed by an evil spirit), and the two soon fall in love. He escaped death on his wedding day by burning the insides of a fish, the smoke of which drove the murderous evil spirit away.

SONG OF THE THREE HOLY CHILDREN --- This consists of a hymn (written about 200 BC) and a prayer (written about 160 BC). It is an addition to the OT book of Daniel, and was supposed to be inserted between Daniel 3:23 and 3:24. It purports to be the prayer of the three men in the fiery furnace, and their song of praise for deliverance.

ECCLESIASTICUS (200 BC) --- This is also known as The Wisdom of Jesus, the Son of Sirach. This work is an ethical treatise extolling the virtue of wisdom. It is very similar to the OT book of Proverbs, and is the longest of all the Apocryphal writings. It is also the only one with a known author. It deals with a wide variety of practical subjects, and gives rules for conduct in all areas of civil, religious, and domestic life. It is fascinating reading, and gives a great deal of sound spiritual advice.

THE MACCABEAN WRITINGS

JUDITH (150 BC) --- This book is a historical romance about a rich, beautiful, devout Jewish widow who delivered her people from the Assyrian commander Holofernes, who was besieging her city of Bethulia. Risking great personal danger, she made her way to his tent, seduced him and got him drunk, and then cut his head off with his own sword. She brought his head back to her city to show that God had delivered the people from his hand. This is somewhat reminiscent of the account of Jael and Sisera in Judges 4:17-22.

ADDITIONS TO THE BOOK OF ESTHER (140 - 130 BC) --- The OT book of Esther never mentions the name of God. This caused some of the writers who translated the Hebrew Scriptures into the Greek language (the Septuagint) to believe that an error had occurred somewhere with regard to this book. As a result, some of the Alexandrian Jews who did the work of translating Esther into Greek added 107 verses -- placing them in six different locations throughout the book of Esther. These 'pious insertions' mention the name of God, prayer unto God, and other matters 'left out' of the original. This was done in an effort to 'spiritualize' the book of Esther. These additions were later gathered and grouped together by Jerome (340 - 420 AD), one of the great scholars of the early centuries of the church's history, and also the man who translated the Bible into Latin -- The Latin Vulgate.

BEL AND THE DRAGON (150 BC) --- This is another unauthorized addition to one of the books of the OT canon: the book of Daniel. It is one of the world's oldest detective stories. The purpose was to ridicule idolatry, and to discredit heathen priests and their work.

THE POST-MACCABEAN WRITINGS

I MACCABEES (90 - 70 BC) --- This book is an extremely valuable historical work on the famous Maccabean period, and it discusses events relating to the heroic struggle of the Jewish people for liberty and independence. It begins with the rise of Antiochus Epiphanes to the throne (175 BC) and ends with the death of Simon (135 BC).

II MACCABEES (50 BC) --- This is also an account of the Maccabean struggle, but it confines itself to the period 175 to 160 BC. It professes to be an abridgment of a five volume history written by Jason of Cyrene. Although far less objective and historical than I Maccabees, and written from the Pharisaic viewpoint, it nevertheless does stress the miraculous nature of the Jewish struggle and displays the power of God at work on their behalf.

Septuagint Apocrypha I Rejected Scriptures Fulfilled

THE HISTORY OF SUSANNA (1st - 2nd century BC) --- This book is recognized by most scholars as one of the great short stories of world literature. It is another inauthentic addition to the OT book of Daniel. It relates how the godly wife of a wealthy Jew in Babylon was falsely accused of adultery and sentenced to death, and how she was ultimately cleared by the wisdom of Daniel.

THE WISDOM OF SOLOMON (40 AD) --- Some scholars disagree with Oesterley's date of 40 AD for the composition of this work, feeling it was more likely produced by an Alexandrian Jew between 150 - 50 BC. It is very similar to parts of the books of Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes. It is a fusion of Hebrew thought and Greek philosophy in which the author seeks to prevent the Jews in Egypt from falling into skepticism, materialism, and idolatry. He also seeks to teach his pagan readers the Truths of Judaism and the folly of heathenism. However, like Plato, this book teaches the pre-existence and inherent immortality of the soul, and that the body is nothing more than an evil prison in which this so-called 'immortal soul' is trapped until its release at death. It was during the 'intertestamental' period that this false doctrine began to rise in prominence.

BARUCH (70 AD) --- This work purports to have been written by Jeremiah's scribe Baruch, who is said in the book to be spending the last years of his life in Babylonian captivity. It is addressed to the exiles, and shows that the tragedies which befell Jerusalem were a just recompense for the sins which they committed against God, and for their neglect of divine wisdom. It also contains a message of comfort and hope for the exiles; stating they will soon be restored to their homeland. It is the only one of the Apocryphal books which comes close to having the same spirit as the OT prophetic books. It consists largely of paraphrases of passages in the books of Jeremiah, Daniel, and other OT prophetic books.

II ESDRAS (100 AD) --- This is also known as IV Esdras (in the Latin Vulgate). It purports to contain seven apocalyptic revelations given to Ezra in Babylon which deal with God's government of the world, a coming new age, and the restoration of certain lost Scriptures.

THE PRAYER OF MANASSEH (1st or 2nd century BC) --- This work claims to be the prayer of King Manasseh of Judah, who was taken to Babylon where he repented of his idolatry (II Chronicles 33). In II Chron. 33:19 mention is made of a prayer he prayed while in Babylon, and which was said to have been written down and placed in the records of Hozai. This is supposedly that prayer.

The word 'Septuagint' comes from the Latin word Septuaginta which means 'Seventy.' One will often see the symbol LXX used to designate this work (which is simply the number seventy in Roman numerals). The name comes from the belief that the work on this Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures was completed in 70 days by 70 scholars. Most biblical scholars, however, set the number of days and translators at 72. The Septuagint is an ancient translation of the OT Hebrew Scriptures into the Greek language for the benefit of the Greek speaking Jews of the Dispersion.

The Septuagint With Apocrypha Pdf

There are many theories as to the origin of the LXX, but the most likely is the one based upon the ancient document known as The Letter of Aristeas. The earliest writer to mention this document by name was Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews, Book 12, Chapter 2, Sections 2-3). This document is extant today in 23 different Greek manuscripts dating from the 11th century AD forward. The first printed edition of The Letter of Aristeas was the Latin translation of Matthias Plamerius of Pisa, which was incorporated into the first Latin Bible to be published in Rome. This letter claims to present an historical account of the origin, purpose, and outcome of the mission of Aristeas to the High Priest Eleazer at Jerusalem during the reign of Ptolemy II of Egypt (285 - 246 BC). The king desired to acquire copies of all the books in the world for his massive library. In order to include a copy of the Jewish Law (the Pentateuch ..... the first five books of the OT writings), a translation from the Hebrew language into the Greek was necessary.

Six elders/scholars from each of the twelve tribes of Israel (72 men), who were to be 'men of exemplary life and learned in the Law,' were selected to produce this translation. They were also required to be noted scholars in the fields of both Hebrew and Greek. These 72 scholars were taken by a man named Demetrius to the island of Pharos. Here, in a secluded area by the sea, they were commissioned to translate the Jewish books of Law into the Greek language for the king's library. They were provided with all the materials necessary to carry out this task.

The work was completed in just 72 days, according to Aristeas, 'as if this coincidence had been the result of some design!' Demetrius then assembled the Jewish community of Alexandria, and, with the translators present, this new Greek version of the Law was read to the people. The translators were then applauded for their great service to the people of the Dispersion. It was agreed that the translation had been executed 'well and with piety,' and it was further agreed upon that a curse would be pronounced upon any who dared to alter the text by addition, omission, or transposition.

The Letter of Aristeas does not mention whether there was ever any work done by these scholars on the remainder of the OT writings. The king had simply requested a translation of the Law; no mention was made of him desiring any of the other Hebrew Scriptures for his library. Several decades later, however, in the prologue to the Apocryphal book of Ecclesiasticus, the author stated that the remainder of the OT Scriptures had indeed been translated into Greek --- 'For words spoken originally in Hebrew are not as effective when they are translated into another language. That is true not only of this book but of the Law itself, the prophets and the rest of the books, which differ no little when they are read in the original.' It is safe to assume, then, that long before the Christian Era the Jews of Alexandria were in possession of the entire Old Covenant writings in the Greek language.

As is true of every version of the Scriptures that has ever been produced, in time critics arose to condemn this work. They either felt it was inaccurate, poorly done, or simply felt it did not meet their needs. Some just didn't like change, and wanted to go back to the original. Others, over the years, made attempts to produce a superior translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. Several of the more prominent versions, and their authors, are:

AQUILA --- This man was related to the Emperor Hadrian (117 - 138 AD), and was the Emperor's construction superintendent overseeing several building projects in Jerusalem. While in Jerusalem, Aquila was converted to Christianity by a group of believers who had recently returned from Pella. However, when he refused to abandon his practice of astrology, the church withdrew their fellowship from him. He then demonstrated his contempt for the church by submitting to circumcision and embracing the teachings of the Jewish rabbis.

As one of his projects, he set out to produce a new translation of the OT writings into the Greek language which would be written in such a way as to not be compatible with the teachings of Christianity. This is what some today might refer to as a perversion, rather than a version, of the Scriptures. It was a translation intentionally designed to support a particular religious view, even though it was done at the expense of accuracy and honesty.

As one might expect, Aquila's version received wide approval from the Jews (many of whom were also, like Aquila, unimpressed with the Christian faith, and who saw this 'version' as an effective weapon to be used against it). By the time of Origen (184 - 254 AD), Aquila's version was trusted implicitly, and was used by most all Jews who did not speak Hebrew. It had, in effect, replaced the LXX in Jewish communities of the Dispersion. In the 4th and 5th centuries (as is indicated in the writings of Jerome and Augustine) it was also the version of preference among the native Jews. Even the Emperor Justinian (483 - 565 AD) got involved in the support of this version. When regulating the public reading of the Scriptures in the Jewish synagogues, he declared it 'expedient to permit the use of Aquila.'

THEODOTION --- According to Irenaeus (b. 115 AD), Theodotion was a proselyte to Judaism, and came from the city of Ephesus. He produced more of a revision of the LXX than an independent translation. The major defect of his version was his habit of transliterating Hebrew words rather than translating them. A scholar by the name of Field cites 90 such Hebrew words that Theodotion transliterates for no apparent cause. Although this practice would be no problem to one who knew both Hebrew and Greek, it nevertheless could cause a great deal of confusion to one who only knew Greek.

SYMMACHUS --- According to Eusebius (260 - 339 AD), this man was an Ebionite, a view which is also confirmed by Jerome (340 - 420 AD). The aim of Symmachus in his translation, as Jerome perceived it to be, was to express the sense of the Hebrew text, rather than trying to attempt a literal word-for-word rendering. He sought to 'clothe the thoughts of the OT in the richer drapery of the Greek tongue' (H.B. Swete).

ORIGEN (184 - 254 AD) --- Origen was one of the great scholars of the early church, and had tremendous knowledge of both Hebrew and Greek. Through extensive study he soon began to realize that in many places the text of the LXX differed significantly from the Hebrew text of his day. Origen felt the church needed to possess a text of the LXX 'in which all additions to the Hebrew text should be marked with an obelus, and in which all that the LXX omitted should be added from one of the other versions and marked with an asterisk. He also indicated readings in the LXX which were so inaccurate that the passage ought to be changed for the corresponding one of another version.' With this goal in mind, Origen produced the two great works --- the Hexapla and the Tetrapla, which were divided into eight and four columns respectively. This was a kind of ancient forefather to our 'parallel versions' of today.

There were two other early attempts to revise the LXX, aside from those mentioned above. In the early part of the 4th century AD, Lucian, a presbyter at Antioch, and Hesychuis, an Egyptian bishop, both undertook similar labors. These two revisions were used primarily in the Eastern churches. From the 4th century AD onward there were no significant attempts to revise the text of the LXX, or to correct the inaccuracies of the various extant copies.

The LXX had a great impact upon the NT writings. When the NT writers quoted from the OT, they did so far more often from the LXX than they did from the Hebrew texts available to them. 'The careful student of the NT is met at every turn by words and phrases which cannot be fully understood without reference to their earlier use in the Greek OT. It has left its mark on every part of the NT, even in chapters and books where it is not directly cited. In its literary form and expression the NT would have been a widely different book had it been written by authors who knew the OT only in the original Hebrew' (Swete).

Is the Apocrypha inspired scripture?

The term apocrypha has several meanings. From its Greek root, it means hidden, or concealed. However, it also referred to a book whose origin was unknown. Over time, this term came to be used to describe any book that was non-canonical. Today, due to the apocryphal books included in the Catholic Bible, most Protestants understand this term to refer to those books in the Catholic Bible that are not in the Protestant Bible.

Since the Catholic church believes it is infallible, and since they state that the Council of Trent issued infallible decrees, and since at the Council of Trent the Catholic church “infallibly” declared the apocryphal books to be canonical (i.e., God breathed Scripture), it is worth looking at these books and the reasons why the Jews and Protestants do not include them in their OT canon.

At Trent (Session IV), the Catholic church explicitly named the books of both the OT and NT: “It [the Council] has thought it proper, moreover, to insert in this decree a list of the sacred books, lest a doubt might arise in the mind of someone as to which are the books received by this council.” Going even further, the Council of Trent pronounced that those who do not accept the apocryphal books as Scripture are accursed:

“If anyone does not accept as sacred and canonical the aforesaid books in their entirety and with all their parts, as they have been accustomed to be read in the Catholic Church and as they are contained in the old Latin Vulgate Edition, and knowingly and deliberately rejects the aforesaid traditions, let him be anathema.”

If one believes the Catholic church is infallible, then it would be very important to follow their decree so as not to be anathematized (i.e., accursed). As we examine the apocryphal books, however, we’ll see that the Catholic church is not only not infallible, they are in gross error to include the apocryphal books.

Before we examine these books, it’s important to point out how we received the apocryphal books. The original OT canon was Jewish, and contained the twenty two books (the same thirty nine in today’s Protestant Bible). This canon was known as the Palestinian canon. When the Hebrew OT was translated into Greek (the Septuagint) in Alexandria, Egypt, included in the canon were fifteen books known as the Apocrypha. These were likely included due to the tradition of many churches viewing these books as “useful”, but not canonical, as we will see. It should also be noted that not all of these books were accepted by the Council of Trent. Per Vlach:

“Of the fifteen books mentioned in the Alexandrian list, twelve were accepted and incorporated into the Roman Catholic Bible. Only 1 and 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh were not included. Though twelve of these works are included in the Catholic Douay Bible, only seven additional books are listed in the table of contents. The reason is that Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah were combined into one book; the additions of Esther were added to the book of Esther; the Prayer of Azariah was inserted between the Hebrew Daniel 3:23 and 24; Susanna was placed at the end of the book of Daniel (ch. 13); and Bel and the Dragon was attached to Daniel as chapter 14.”

Vlach also provides a very useful summary of each of these fifteen books, as shown below.

1. The First Book of Esdras (150—100 B.C.) (not included in Catholic Bible) – This work begins with a description of the Passover celebration under King Josiah and relates Jewish history down to the reading of the Law in the time of Ezra. It reproduces with little change 2 Chronicles 35:1—36:21, the book of Ezra and Nehemiah 7:73—8:13a. It also includes the story of three young men, in the court of Darius, who held a contest to determine the strongest thing in the world. 1 Esdras has legendary accounts which cannot be supported by Ezra, Nehemiah or 2 Chronicles.

2. The Second Book of Esdras (c. A.D. 100) (not included in Catholic Bible) Differs from the other fifteen books in that it is an apocalypse. It has seven revelations (3:1—14:48) in which the prophet is instructed by the angel Uriel concerning the great mysteries of the moral world. It reflects the Jewish despair following the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70.

3. Tobit (c. 200—150 B.C.) The Book of Tobit describes the doings of Tobit, a man from the tribe of Naphtali, who was exiled to Ninevah where he zealously continued to observe the Mosaic Law. This book is known for its sound moral teaching and promotion of Jewish piety. It is also known for its mysticism and promotion of astrology and the teaching of Zoroastrianism (The Bible Almanac, eds. Packer, Tenney and White, p. 501).

4. Judith (c. 150 B.C.) Judith is a fictitious story of a Jewish woman who delivers her people. It reflects the patriotic mood and religious devotion of the Jews after the Maccabean rebellion.

5. The Additions to the Book of Esther (140-130 B.C.) 107 verses added to the book of Esther that were lacking in the original Hebrew form of the book.

6. The Wisdom of Solomon (c. 30 B.C.) This work was composed in Greek by an Alexandrian Jew who impersonated King Solomon.

7. Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach (c. 180 B.C.) This book is the longest and one of the most highly esteemed of the apocryphal books. The author was a Jewish sage named Joshua (Jesus, in Greek) who taught young men at an academy in Jerusalem. Around 180 B.C. he turned his classroom lectures into two books. This work contains numerous maxims formulated in about 1,600 couplets and grouped according to topic (marriage, wealth, the law, etc.).

8. Baruch (c. 150-50 B.C.) This book claims to have been written in Babylon by a companion and recorder of Jeremiah (Jer. 32:12; 36:4). It is mostly a collection of sentences from Jeremiah, Daniel, Isaiah and Job. Most scholars are agreed that it is a composite work put together by two or more authors around the first century B.C.

9. The Letter of Jeremiah (c. 300-100 B.C.) This letter claims to be written by the prophet Jeremiah at the time of the deportation to Babylon. In it he warns the people about idolatry.

10. The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Young Men (2nd— 1st century B.C.) This section is introduced to Daniel in the Catholic Bible after Daniel 3:23 and supposedly gives more details of the fiery furnace incident.

11. Susanna (Daniel 13 in the Catholic Bible) (2nd — 1st century B.C.) In this account, Daniel comes to the rescue of the virtuous Susanna who was wrongly accused of adultery.

12. Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14 in the Catholic Bible) (c. 100 B.C.) Bel and the Dragon is made up of two stories. The first (vv. 1-22) tells of a great statue of Bel (the Babylonian god Marduk). Supposedly this statue of Bel would eat large quantities of food showing that he was a living god who deserved worship. Daniel, though, proved it was the priests of Bel who were eating the food. As a result, the king put the priests to death and allowed Daniel to destroy Bel and its temple. In the second story (vv. 23-42), Daniel, in defiance of the king, refuses to worship a great dragon. Daniel, instead, asks permission to slay the dragon without “sword or club” (v. 26). Given permission, Daniel feeds the dragon lumps of indigestible pitch, fat and hair so that the dragon bursts open (v. 27).

Septuagint Bible Pdf

13. The Prayer of Manasseh (2nd or 1st century B.C.) (Not in Catholic Bible) This work is a short penitential psalm written by someone who read in 2 Chronicles 33:11-19 that Manasseh, the wicked king of Judah, composed a prayer asking God’s forgiveness for his many sins.

14. The First Book of the Maccabees (c. 110 B.C.) “The First Book of Maccabees is a generally reliable historical account of the fortunes of Jewish people between 175 and 134 B.C., relating particularly to their struggle with Antiochus IV Epiphanes and his successors. . . . The name of the author, a patriotic Jew at Jerusalem is unknown” (Metzger, p. 169). The book derives its name from Maccabeus, the surname of a Jew who led the Jews in revolt against Syrian oppression.

Septuagint Apocrypha I Rejected Scriptures John Hagee

15. The Second Book of the Maccabees (c. 110-70 B.C.) This book is not a continuation of 1 Maccabees but an independent work partially covering the period of 175-161 B.C. This book is not as historically reliable as 1 Maccabees.

Why Christians Reject the Apocrypha

Why do Christians reject the Apocryphal books as canonical? There are at least eight good reasons why Christians reject the apocryphal books as being included in the OT canon. These include history and evidence from some of the books themselves.

Septuagint English Bible

First, no apocryphal books were written by a prophet. All of the OT Scriptures were written by prophets, while none of the apocryphal books were; therefore, the apocryphal books are not canonical. Scripture attests to this view in that the OT is referred to as the Scriptures of the prophets. Specific references include (with emphases added):

So we have the prophetic word made more sure, to which you do well to pay attention as to a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star arises in your hearts. (2 Peter 1:19)

But now is manifested, and by the Scriptures of the prophets, according to the commandment of the eternal God, has been made known to all the nations, leading to obedience of faith; (Romans 16:26)

As He spoke by the mouth of His holy prophets from of old. (Luke 1:70)

But Abraham said, 'They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.” (Luke

16:29)

Then beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, He explained to them the

things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures.” (Luke 24:27)

God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in

many ways (Hebrews 1:1)

More Scripture could be quoted, but clearly, the prophets are equivalent to the OT, as God spoke His word solely through prophets. Furthermore, it is generally agreed (especially among the Jews) that Malachi was the last prophet before John the Baptist. Yet most of the writers of the apocrypha lived after Malachi. In addition, the apocrypha was not written in Hebrew as was all of the OT (most were written in Greek). If inspired, it would only make sense that the writers would write in the language of Israel.

Second, the apocryphal books were not accepted by the Jews as part of the OT. If these books were part of the canonical OT, then surely Jesus would have criticized the Jews for excluding them from Scripture, yet He never does.

Third, Jesus and the apostles never quote from the apocryphal books. The OT testifies of Christ, and He gives testimony to the validity of the OT by quoting from many of its books. The apostles, likewise, quote from the OT. Yet they never quote from any of the apocryphal books.

Why does Jude quote the Book of Enoch then? This book was not one of the apocryphal books of which we’re speaking; rather, it was part of the Pseudepigrapha, which were a set of supposed scripture that were universally rejected as false writing. Nevertheless, Jude mentions the book because it was well known in his day, and evidently it contained some useful information despite not begin inspired scripture.

Just because Jude quotes this book does not mean Enoch is inspired. If that logic were true, then we’d have to say that heathen writings are also inspired. This is because Paul quotes from certain heathen poets, such as Aratus (Acts 17:28), Menander (1 Corinthians 15:33), and Epimenides (Titus 1:12). Just because Scripture quotes a truthful source does not make that source automatically inspired Scripture.

Fourth, many Jewish scholars and early church fathers rejected the apocryphal books as canonical. Jewish writers such as Philo and Josephus, and the rabbis at the Council of Jamnia all rejected the apocryphal books as canonical. Most of the early church also rejected them, including Origen, Athanasius, Hilary, Cyril, Epiphanius, Ruffinus, and Jerome. Interestingly, cardinal Cajetan, the man the Catholic church sent to debate Luther, also rejected these books as canonical. In his commentary of the history of the OT, he writes the following:

“Here we close our commentaries on the historical books of the old Testament. For the rest (that is, Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees) are counted by St Jerome out of the canonical books, and are placed amongst the Apocrypha, along with Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus, as is plain from the Prologus Galeatus. Nor be thou disturbed, like a raw scholar, if thou shouldest find any where, either in the sacred councils or the sacred doctors, these books reckoned as canonical. For the words as well of councils as of doctors are to be reduced to the correction of Jerome. Now, according to his judgment, in the epistle to the bishops Chromatius and Heliodorus, these books (and any other like books in the canon of the bible) are not canonical, that is, not in the nature of a rule for confirming matters of faith. Yet, they may be called canonical, that is, in the nature of a rule for the edification of the faithful, as being received and authorized in the canon of the bible for that purpose. By the help of this distinction thou mayest see thy way clearly through that which Augustine says, and what is written in the provincial council of Carthage.”

This is interesting because not only is cardinal Cajetan a Catholic, he also provides evidence for how some viewed the apocryphal books as canonical, the most famous of which is Augustine. There is other evidence from Augustine that corroborate this view, meaning when he said the apocrypha was canonical, he did not mean it in the sense of being inspired. Rather, it was meant in the sense of being useful for edification.

Indeed, Athanasius, after naming the twenty two Hebrew OT books (thirty nine in Protestant Bibles), says “But, besides these, there are also other non-canonical books of the old Testament, which are only read to the catechumens.”, and then he names the apocryphal books. This is why Jerome included those books in the Latin Vulgate, which he translated.

Fifth, some apocryphal books contain many historical and geographical inaccuracies. As we have shown in our prior study on the inspiration of Scripture, the Bible does not contain such inaccuracies. These errors prove the books that contain them are non- canonical. Some of the errors are shown below:

- There are several inconsistencies in the additions to Esther, one of which in chapter 6 mentions Ptolemy and Cleopatra. Both lived after the times of Mordecai, so including these two later historical figures clearly shows this addition was written well after Esther was completed. In addition, the added chapters were written in Greek, not Hebrew.

- In the book of Judith, Holofernes is incorrectly described as the general of “Nebuchadnezzar who ruled over the Assyrians in the great city of Ninevah” (1:1). In truth, Holofernes was a Persian general, and Nebuchadnezzar was king of Babylon.

Sixth, the apocryphal books often contradict Scripture. Examples include:

- The Book of Tobit teaches magic (Tobit 6:4,6-8). The Bible clearly condemns magical practices such as this (consider Deuteronomy 18:10-12; Leviticus 19:26,31; Jeremiah 27:9; Malachi 3:5).

- 2 Maccabees 12:43-45 states: “He also took up a collection ... and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. ... For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen asleep would arise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead ... Therefore he made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin.” This teaches prayers for the dead, as well as salvation by works, both of which contradict Scripture. Hebrews 9:27 makes clear that judgment comes after death, while numerous Scriptures clearly show that salvation is solely by faith in Christ alone.

- The Book of Tobit 12:9 states: “For almsgiving delivers from death, and it will purge away every sin.” This clearly contradicts Scripture (e.g., Leviticus 17:11, Titus 3:5, Romans 4 and 5, etc.).

Seventh, the apocryphal books were never accepted by the church until the Council of Trent. Roughly 1,500 years after these books were written, the Catholic church decided to “officially” recognize the apocrypha as Scripture. As we’ve seen above, these books were not accepted as canonical Scripture by either the Jews or the early Christian church. It is clear that the Catholic church adopted these books as canonical in opposition to Protestantism, as some of the apocrypha (falsely) supported Catholicism’s teaching regarding salvation.

And finally, no apocryphal book makes the claim that it is the word of God. While most OT books do claim to be God’s word, none of the apocrypha claim this status.

While some of the apocryphal books are useful, especially from a historical perspective, it’s clear they are not inspired, and therefore do not belong in the OT canon. We encourage believers to read these books, however, so they can judge for themselves as well.

You may also be interested in another article on why we can trust the BIble.

do you have a question you need an answer to?

Bible answers

Submit a Question

Related Questions

QHow were the 66 books of the Bible selected?

06.04.2014

QAre Roman Catholics truly Christian?

11.02.2015

QWhen is the Catholic pope’s proclamations considered “infallible”?

09.14.2013